And with this, a great delight as an awakening or sort of resurrection might be expected to have. It was like seeing frozen figures thawing.

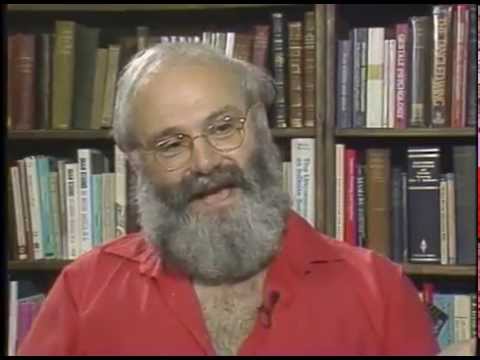

I remember one patient stroking leaves and looking at the nightlights of New York on the horizon and everything was a source of delight and gratitude. There was great joy and a sort of lyrical delight in the world which had been given back. I thought of the Sleeping Beauty, of Rip Van Winkle and all the others in a sort of way. There was a quality of a fable about this in the spring in the summer of '69. There would be the beginnings of spontaneous movement, the beginnings of speech, the beginnings of attention and looking around, the beginnings of animation. With the patients who came out more slowly, one would see over a period of days a sort of melting of the rigidity of the frozen picture. Some of the patients came out more slowly, some instantly changed. They tend to warm up gradually, maybe one had seen, as it were, a built-in tendency to suddenness with these patients in the way in which they might suddenly snap out of things if there was a fire engine or a sneeze or something like this. Patients with ordinary Parkinson's disease don't respond in this sudden way. The suddenness was incredible and nothing which I had read about gave me any hint of this. On the sudden and gradual reactions to the L-dopa So everything looked frozen, and then, very suddenly, sometimes one of these patients would be released from this state and would speak and move, then you could see what a vivid, alive, real person was there, imprisoned in a sort of way by some strange physiological change. They were motionless figures who were transfixed in strange postures - sometimes rather dramatic postures, sometimes not - with an absolute absence of motion, without any hint of motion.

I suppose the first impression was that I had entered a museum or waxwork gallery. On the catatonic state of the patients he described in Awakenings

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)